There’s a growing squeeze for land but not for what you think. It’s not for housing or agriculture or factories. It’s for offsets. By Dr Jez Weston and Lucie Greenwood

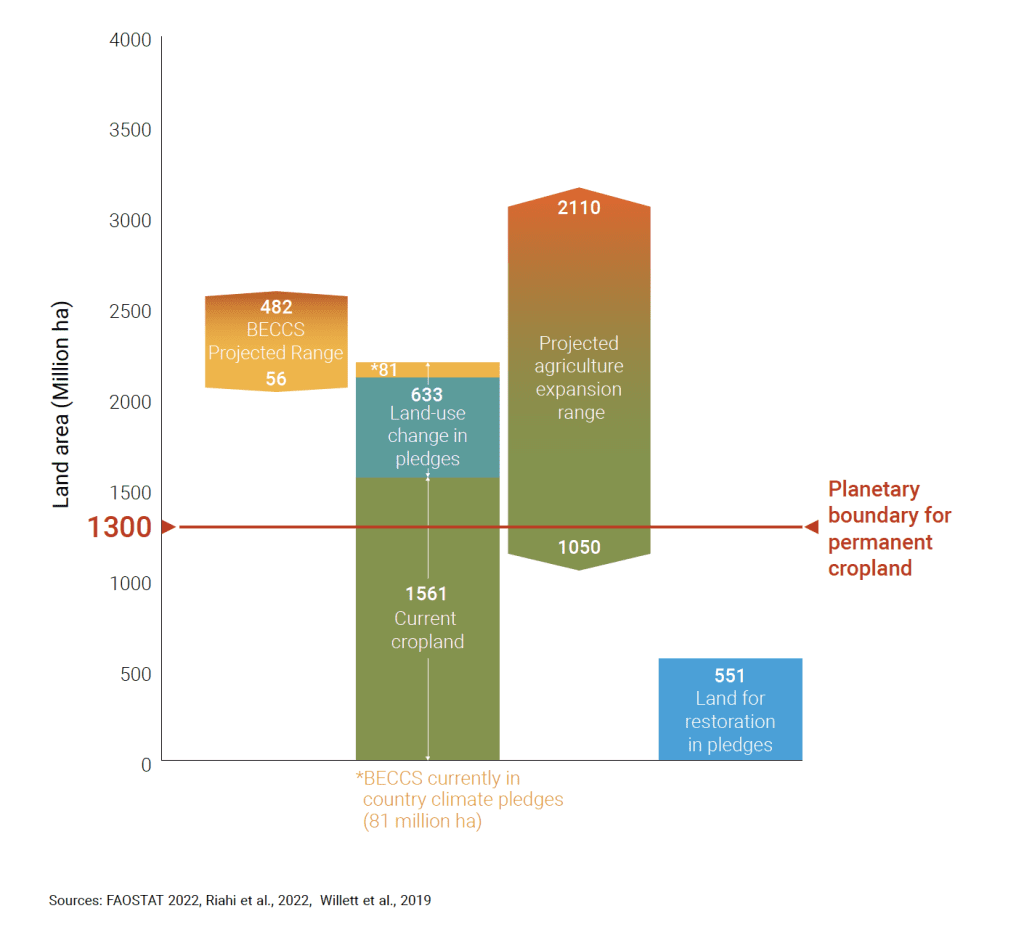

The “Land Gap” report by researchers from the Universities of Melbourne, Copenhagen, Lund and others, summarised the overall demand for offset across the globe. It’s bad news – the combined pledges for land to meet national emissions targets sum to 1.2 billion hectares. That’s equivalent to all current global cropland or four times the area of India. That’s a pretty big land gap.

There simply isn’t enough spare land internationally for rich nations to rely on overseas offsets. The demand so greatly exceeds the supply that any market is likely to be highly dysfunctional – New Zealand may not be able to buy sufficient offsets at any price.

That land gap means that the effort for meeting our national emissions targets has to fall back onto the other two components – more ambitious savings in domestic gross emissions and more carbon sequestration from domestic forestry.

New Zealand’s carbon debt

New Zealand’s plan to meet our targets for emissions reductions relies on three components – reducing gross emissions in New Zealand, increasing forestry mitigation in New Zealand, and offshore mitigation. Current plans to balance the cost and difficulty of these three leaves us with the third taking up much of the slack – over fifty million tonnes of emissions, according to the Climate Change Commission. That’s 9% of our emissions or 70% of our planned emissions reductions.

Buying offsets overseas will cost the New Zealand government maybe $10 billion, maybe $30 billion by 2030, depending upon whose estimates you believe. That’s a huge amount. Yet there’s a more worrying problem here – which nations will we pay to plant trees and to manage their ecosystems to store carbon for us?

We can be far more ambitious and scientific about forestry as a climate solution with economic and management models other than pine monocultures.

The problem is that plenty of other rich, high-emissions nations expect to do exactly the same thing. That’s entirely understandable. Buying offsets from overseas is a cookie-cutter solution – no need to increase domestic efforts. Instead, the politically-easy solution is to shift this mitigation burden away from domestic emitters onto overseas land, local communities and ecosystems all out of sight and out of mind.

In essence, the rich world is expecting that carbon indulgences will be available for purchase. Or will they? Given that so many nations plan to purchase offsets, what is the sum effect of all of these rich nations pledging to use land in poorer nations?

If you really must buy credits …

At the Climate VC Fund, we believe reducing gross emissions through technology and behaviour change can be faster and more ambitious than others expect. Still, we recognise that this will be only part of the solution.

So how much more can domestic forestry do? The Government’s draft Industry Transformation Plan seeks to create high-value and resilient forestry and wood processing, following the “right tree right place right purpose” ideal. There are strong opportunities to improve our current approaches to forestry. Permanent pine monocultures may be the fastest but they are not the best from a carbon storage perspective, given risks from extreme weather and disease. Nor do they appear particularly useful through a food security or biodiversity lens.

Less discussed in New Zealand is the need for a far more robust understanding of the carbon sequestered by forestry. Our carbon accounting methods fail to factor in the reality that forests exist in an ecosystem, soil and all, with much of the carbon stored in the soil. Lost soil carbon is a given in clear-fell rotation forestry. On steeper land, topsoil can be lost to erosion and landslides, and, in all cases, heavy machinery and exposed soil causes losses. Some estimates imply that soil carbon losses after clear-felling largely offset biomass carbon accumulation. The upshot is that we risk overestimating carbon sequestered from our forestry estate and miss our climate targets.

We can be far more ambitious and scientific about forestry as a climate solution with economic and management models other than pine monocultures. To be fair, the Government’s Climate Emergency Response Fund initiatives this year include large investments into better understanding of forest soil carbon and forest management and native forestry. These investments should enable more climate- and ecosystem-smart forestry.

By reframing the cost as opportunity, New Zealand could treat the carbon offsets as an investment in a greener, cleaner, economy

All of this is not to say that New Zealand should avoid all offshore mitigation – it means we should go into it with a realistic and informed strategy, recognising that land will be scarce and that this is an area full of pitfalls. One option for offshore offsetting is to support efforts in neighbouring Pacific Island countries to bolster nature-based solutions, such as the protection of indigenous forests and marine ecosystems. Doing so aligns with our commitment to support climate action in the Pacific that enhances local environments and livelihoods.

Several pilot projects in the Solomon Islands, for example, seek to give communities an alternative income to selling logging rights to foreign companies. These pilots develop local governance to enable communities to protect and regenerate forests on their land, and to earn and direct carbon revenue into community-led economic developments, grounded in local values and worldviews.

Our enduring partnerships with Pacific nations could provide a more ethical and sustainable source of credible carbon credits. However, the size of these small island nations means that they are likely to serve only a fraction of our offsetting needs.

The biggest wins remain here in New Zealand as we take responsibility for our own emissions. But herein lies the opportunity. By reframing the cost as opportunity, New Zealand could treat the carbon offsets as an investment in a greener, cleaner, economy. That could include funding that accelerates the adoption of low-emissions technology. Or adapting infrastructure for a heated, stormy climate. Or funding programmes to ensure a just transition for affected communities. By controlling the destination and purpose of our carbon spend, New Zealand can deliver on its net-zero targets and simultaneously fund its transition to a low-emissions economy.

Jez Weston is a co-founder of the CVFC and Lucie Greenwood is a member of the Climate Impact Committee of the CVCF and a senior associate at The Connective