Agriculture is facing a huge problem with climate change. It’s also facing opportunities for growth and leadership. So what’s the hold up, asks Rohan MacMahon.

As I write these words Cyclone Gabrielle’s hefty impact on New Zealand is fully evident. Houses have been wrecked and businesses destroyed. Lives have been lost, and many are still missing. Whole regions like Hawkes Bay and Tairāwhiti are in disarray and the damage bill will run to many billions of dollars.

This latest, climate-change fuelled weather event, is a reminder that New Zealand is highly vulnerable to climate change and must adapt urgently. And it’s a moving target. Until we reach net zero emissions then we will be moving our own goal posts further away from where we are.

We must adapt, while simultaneously reducing our emissions.

In New Zealand’s case, it’s particularly important that we reduce all greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) – not just the carbon dioxide from our cars and factories, but methane from ruminant animals and nitrous oxide from fertiliser use.

Agricultural emissions make up around half of our total GHGs, a much higher proportion than most developed countries. Globally, 17% of GHGs are from agriculture and land use. In Australia it is only 13 and in the US just 9%.

Reducing agricultural emissions has a disproportionate role to play in the climate response. Events such as Cyclone Gabrielle show the impact of rampant GHGs are just as heavy on farming communities as they are on those in towns in cities. We simply can’t afford to ignore agricultural emissions.

One problem, two opportunities

This is important not just because of gross emissions. Companies such as Tesco, and our own trade negotiators, tell us that market access will depend on low-carbon certification in all our exports, including meat and dairy. The downside risk is that we are gradually excluded from international markets because we have failed to mitigate our emissions.

The upside is that a low-emissions ag sector will enhance our reputation as a clean, ethical food producer and will open doors to new customers. The faster New Zealand farmers do this, the faster they get ahead of their global competitors.

Additionally, New Zealand already has a burgeoning agritech sector. Leading the world in low-emission farmtech could open huge areas of growth for IP, R&D and hi-tech companies (like the ones we invest in).

Addressing the one big problem of emissions could provide two opportunities: a more competitive agriculture and a burgeoning agritech sector.

The agri-emissions challenge has been recognised for many years, and was highlighted as a key component of the Zero Carbon Act which was agreed by Parliament in 2019. The final vote of 117-1 indicated that there was at that time a high degree of political agreement to (i) a net zero by 2050 goal for carbon dioxide, and (ii) specific reductions (albeit not to net zero) for biogenic methane from agriculture.

Reducing agricultural emissions is challenging, and the Zero Carbon Act recognises this. As its name suggests, the Act states an aspiration for New Zealand to achieve net zero in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, but for biogenic methane the goal is a more modest reduction of 24% to 47% by 2050.

The Government also agreed to create a separate industry-iwi-government process (known as He Waka Eke Noa) rather than regulating agricultural emissions via the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) in the manner of other GHGs and other industries.

Dragging the chain

Farmers have had research into reducing emissions funded by Government for over 20 years. This is continuing under the current ETS and the Climate Emergency Response Fund, which tags $339m of funds paid to the Government via the ETS towards this research in the period to 2026. Remembering that agriculture is outside the current ETS, this means farmers are receiving a unique benefit – they are being cross-subsidised by other industries for the costs of greenhouse gas research.

In summary, methane emissions on-farm have been treated differently from carbon dioxide emissions in at least three ways, all of which are less stringent to farmers:

- Methane does not have a “net zero by 2050” target;

- Agriculture has a separate industry/ government process rather than the ETS;

- Research funding is provided via the ETS, funded by non-agricultural emitters.

2023 is less than two months old, and already we have seen Cyclone Hale, the Auckland storm of 27th January and Cyclone Gabrielle. Each of these events is likely to have been exacerbated by anthropogenic global warming, including from agricultural emissions.

How many more warnings do we need?

It seems, as many as it takes before we get our act together.

The slow revolution is underway

Sometimes the political and media narrative can make agricultural emissions seem “too hard”. Some groups would certainly like it if the whole topic went away altogether. It won’t – it’s too important.

In fact, far from being “too hard”, there is plenty of activity across both Australia and New Zealand to indicate much lower agricultural emissions are indeed achievable. Here are a few examples:

- Adopting regenerative agricultural practices including organic farming, protecting waterways, tree-planting on low-quality and storm-vulnerable lands etc.;

- Trialling feed supplements & treatments to reduce methane emissions from cattle and sheep, via bromoform/ seaweed (CH4 Global, Rumin8, Ruminant Biotech); or chemical supplement Bovaer;

- Developing methane “vaccines” for ruminant animals;

- Using microbial technology to increase carbon capture in soils (Loam Bio);

- Coating fertiliser pellets, to control the release of nutrients, producing less run-off, lower emissions and higher farm productivity;

- Evolving horticultural practices, for example using Hot Lime Labs as a source of green carbon dioxide for greenhouses, or building indoor “vertical farms” for strawberries to substitute for air-freighted produce;

- Using robotics to improve productivity in horticulture, such as Robotics Plus;

- Deploying new tools to improving herd management and productivity, such as Halter;

- Adopting artificial intelligence-powered technology to improve management of viticulture, such as Cropsy;

- Breeding cattle which have lower emissions using research from the Livestock Improvement Corporation; and

- Investing in research into hot climate crops such as the new Tutti apple by Plant & Food Research.

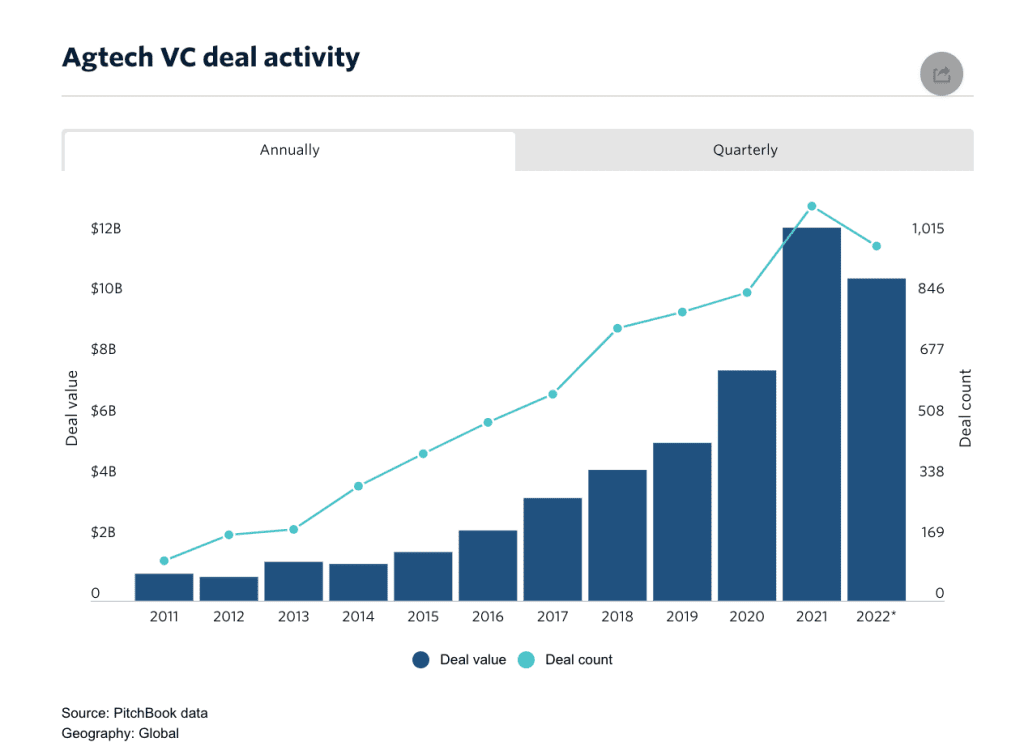

Looking further afield, global data shows healthy levels of venture capital investment in agri-tech, in spite of the challenges the sector faced in 2022. And that’s before you get to food processing, where many manufacturers are investing to reduce energy usage, aided by the New Zealand “Government Investment in Decarbonising Industry” programme, or new food alternatives like plant-based proteins which are booming.

In short, at the Climate VC Fund we see an expanding list of technology options to help reduce agricultural greenhouse emissions. We are interacting with many New Zealand and Australian founders who are working as part of this quiet revolution.

A pricing signal for large agricultural emitters, whether by including agricultural emissions in the ETS or another method, would be helpful in accelerating this process. But farming practices are changing before our very eyes.

As communities around the country work to clean up and repair the damage from recent extreme weather events, it’s yet another stark reminder that we all need to accelerate our response to climate change.

Change is not just possible, it’s already happening. But we can all do more to speed up the process.

We encourage you to get in touch if you would like learn more about the Climate Venture Capital Fund.

Rohan MacMahon is a co-founder of the Climate Venture Capital Fund